Life in a Slave Labor Barrack

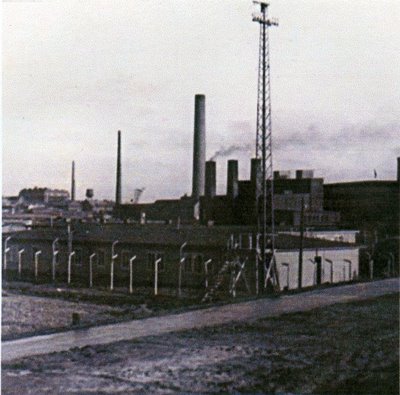

The grim looking structure enclosed by a barbed wire fence was a slave labor barrack at a Focke-Wulf aircraft factory on the west bank of the Weser River near the village of Einswarden in Northern Germany. For seven months it was my home.

The grim looking structure enclosed by a barbed wire fence was a slave labor barrack at a Focke-Wulf aircraft factory on the west bank of the Weser River near the village of Einswarden in Northern Germany. For seven months it was my home.No, I was never a slave laborer for Hitler's Third Reich. While living there shortly after the end of World War II I was a military policeman, an MP. The building itself wasn't bad - two men to a room, a decent shower and latrine - but Germany was a dreary place in the late months of 1945 and the early ones of 1946. On top of that, being only a few miles from the North Sea meant the climate was frightful.

We had two basic jobs that varied from day to day. The toughest of them was riding around in a Jeep patroling the factory complex, which was being used as an ordnance depot, as well as Einswarden and the larger town of Nordenham. The easy one was spending the day or the night in a large guard house at the main gate. We were merely supervisors with the actual work, such as it was, being done by former German soldiers. There was always a dozen of them there, sometimes twice that number, although it took only one man to supervise the traffic coming in or going out.

In the guard house we spent most of the shift talking. This was difficult at times because only one of them was fluent in English and my German was limited in the extreme. In spite of that, as time went by we became pretty good at making ourselves understood. It was easier, though, when the English speaking Muller was there.

Muller had been a paratrooper with an amazing ability to survive. He stood 6-5 or 6-6 and was thin as a fence post, but agile as a gymnast. He had dropped on the day Germany invaded Belgium and again on the island of Crete, where the fighting was prolonged and vicious and the major opposition came from tough and rugged civilians. As a ground soldier he had fought in North Africa, Italy, Normandy and for a couple of years on the Russian front. No man should have lived through all that, but Muller did.

Sometimes at three or four in the morning the Germans would sing their old marching songs. Softly, so as not to attract the attention of any puffed-up American officer. We had many like that, believe me, and eventually they proved to be the downfall of Muller and many of the other guards, but that's a story for another day. I enjoyed that quiet singing and sometimes even hummed along on a chorus or two...hi lee, hi low, ha-ha, hi lee, hi low...

Muller and I became friends. Sometimes I visited his home or we would take walks around the countryside. One night he told me that the other Germans thought I was OK because I was tolerant and friendly. Aside from one man and he hated everyone alive. Perhaps he had reason to because he had returned from the Russian front badly crippled to find that his house was the only one on that side of the river to be destroyed by a bomb - a stray one that wasn't meant to be dropped. But Americans in general, that was another matter. Muller said, "We hate the British and Americans for killing our women and children. We hate the Russians for destroying our army."

I had seen the result of strategic bombing in several large German cities and hated it too. The top brass believed that by killing enough civilians - women, children, babies, the elderly - they would break the will of the German soldiers. Instead it made them fight all the harder. I was glad that I had been an infantryman who fought other soldiers, not those who were helpless. When we did find that civilians had been killed during a firefight, and especially children, it was upsetting to most of us.

How bad was some of that bombing? Terror bombing, there is no other word for it. They say that the atom bomb dropped on Hirishima killed 71,379 people. In the final weeks of the war the conventional bombing of Dresden, Germany, a city without a single military objective, killed at least 135,000. Victory was already assured, there was no reason for it to have happened.

There are those who contend terror bombing was justified because the Germans had bombed London and other British cities. Does that mean that two wrongs make a right? Did the terror bombing kill off the men responsible for the destruction in London? Of course not.

I wonder, too, why it was that not a single bomb fell on that aircraft factory where we lived but across the river in Bremerhaven block after block of residential areas were leveled? That was far from being the only example of the property of multi-national corporations being spared. The results of war aren't always what they seem to be.

<< Home